As Bumaga found out, the protest action was reported to the authorities by a retired woman. A special operation was set up by the police in order to capture Skochilenko. The young woman is now under arrest and will spend a month and a half in jail despite serious health issues.

This is the story of Sasha Skochilenko: Saint Petersburg artist and musician, Bumaga’s former contributor, conscientious citizen.

The police arranged a special operation to arrest Skochilenko. A retired woman reported on her to the authorities

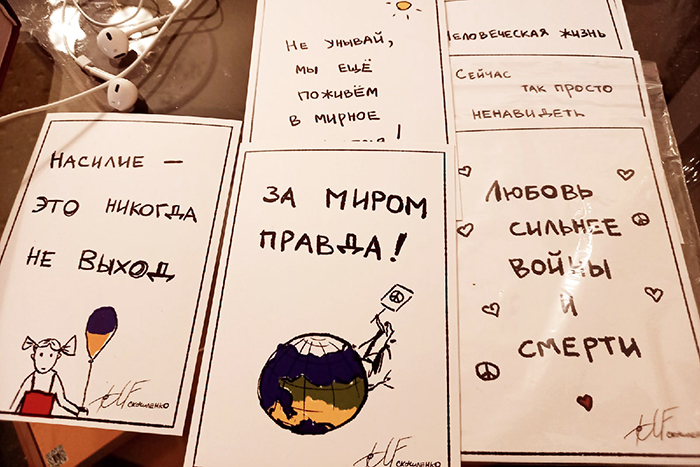

In the evening of March 31, anti-war messages were posted inside a Perekrestok supermarket at the Shkipersky Mall in Vasilievsky Island in Saint Petersburg. They were placed into price label holders on small pieces of paper resembling actual labels.

The false labels were noticed by a client, a 75-year old retired woman, according to Bumaga’s two sources close to the investigation. One of them told us the woman took it to the attorney’s office to “seek justice”. According to the other source, she reported directly to the police.

Information gathered by Bumaga suggests that the law officers spent over ten days questioning the supermarket’s employees and watching CCTV footage to identify and trace the person who posted the labels.

Early on April 11 the law enforcement carried out a special operation. Several officers showed up in the suspect’s apartment located about 900 meters from Perekrestok. We do not know exactly what happened in the apartment, the resident of which turned out to be a friend of Sasha Skochilenko’s.

That morning the 31-years old Skochilenko received a text message from the friend, telling her about a “search for a body” in his apartment and asking her to come over. Sasha was already on her way when the young man texted her: “everything okay”. Skochilenko’s friends believe the messages could have been sent by the police after seizing the man’s phone.

Skochilenko was arrested around 11 AM upon her arrival into the apartment. Bumaga received the news of Sasha’s arrest from her friend around 2 PM of the same day. The young woman could not be reached for over four hours while the police would not comment on her whereabouts.

It was not until later that Skochilenko’s attorney Dmitry Gerasimov found out his client’s own apartment was already being searched. Sasha was then questioned by the police until 12:30 AM of April 12.

Later that day, Gerasimov told Bumaga that Sasha was the target of a criminal investigation on “fake news about the Russian Army” for allegedly replacing Perekrestok’s price labels with anti-war messages. According to the investigation, the woman “publicly distributed deliberately false information about the use of Russian Federation’s military force”.

Charges against Sasha Skochilenko invoke part two of the criminal code’s corresponding article, which means she faces up to ten years in prison. Investigators claim her actions were “motivated by political hatred”.

Documentation provided by the investigation does not mention any evidence of “deliberate falsehood” in the anti-war messages, nor does it elaborate on the “political hatred” motif.

More on the “Fake News about the Russian Army Act” ↓

The act establishing criminal responsibility for spreading “fake news about the Russian Army” was signed into law by president Vladimir Putin on March 4. The law introduced a new article no. 207.3 into the Russian Criminal Code: “Public distribution of deliberately false information of the use of the Russian Federation’s military to defend Russia’s interests and citizens.”

- The article’s Part 1 carries a maximum penalty of 3 years in prison, or a fine between 700 thousand to 1,5 million rubles (roughly 8,400 to 18,000 USD), or up to 1 year of corrective labor, or up to 3 years of forced labor.

- Part 2 covers the acts committed using one’s official position, in a group, involving creation of fraudulent evidence, or motivated by hatred to a social group. Possible sanctions include five to ten years of prison time, 3 to 5 million rubles in fines, and up to five years of forced labor.

- According to Part 3, in case of “severe consequences” caused by such an act the sentence will be as much as ten to fifteen years of imprisonment.

The reason for criminal investigation might be information on killings in Mariupol. But the messages’ content is unknown

Sasha actively protested against the war in Ukraine since the invasion began. She performed at anti-war “Peace Jam” music sessions and made pacifist artworks. This was why the woman’s friends expected a misdemeanor charge for “discrediting the Russian Federation’s Army,” which has been popular lately with the law enforcement. But the reality was different.

“[There’s no misdemeanor charge], because those labels [in earlier misdemeanor cases] were statements against war in general, while in Sasha’s case it’s allegedly about the Russian Army’s actions,” said Skochilenko’s attorney Dmitry Gerasimov as he tried to explain the investigators’ logic to Bumaga.

However, investigation materials provided to the lawyer have no mention of any specific incriminating messages.

According to a post by the Net Freedoms Project, the labels in the case feature information about the bombing of the Mariupol Theatre and civilian deaths in the Ukrainian city. Gerasimov refused to confirm or deny this to Bumaga saying that Sasha did not “remember the labels or the messages in them.”

Sasha had previously designed anti-war stickers saying “Cheer up, we’ll get to live in peaceful times” and “Human life is invaluable”.

“There’s still many people around who don’t know (or remember?) that human life is a miracle, beautiful and precious; that violence is never a solution,” the woman explained.

Sasha’s line of defense is based on her admission of distributing anti-war messages in the store containing information about Russia’s use of military force in Ukraine and its consequences. However, Skochilenko does not agree that the information was false, as the charge implies, according to her lawyer.

Sasha Skochilenko was refused bail by a judge. She has celiac disease, or gluten intolerance

Sasha Skochilenko spent the night of April 12 in a detention cell. As she would later claim in court, she had some sleep but was refused drinking water or a parcel sent to her by her friends. The first hearing of her case was then postponed to the following day, leaving Sasha in jail for another 24 hours.

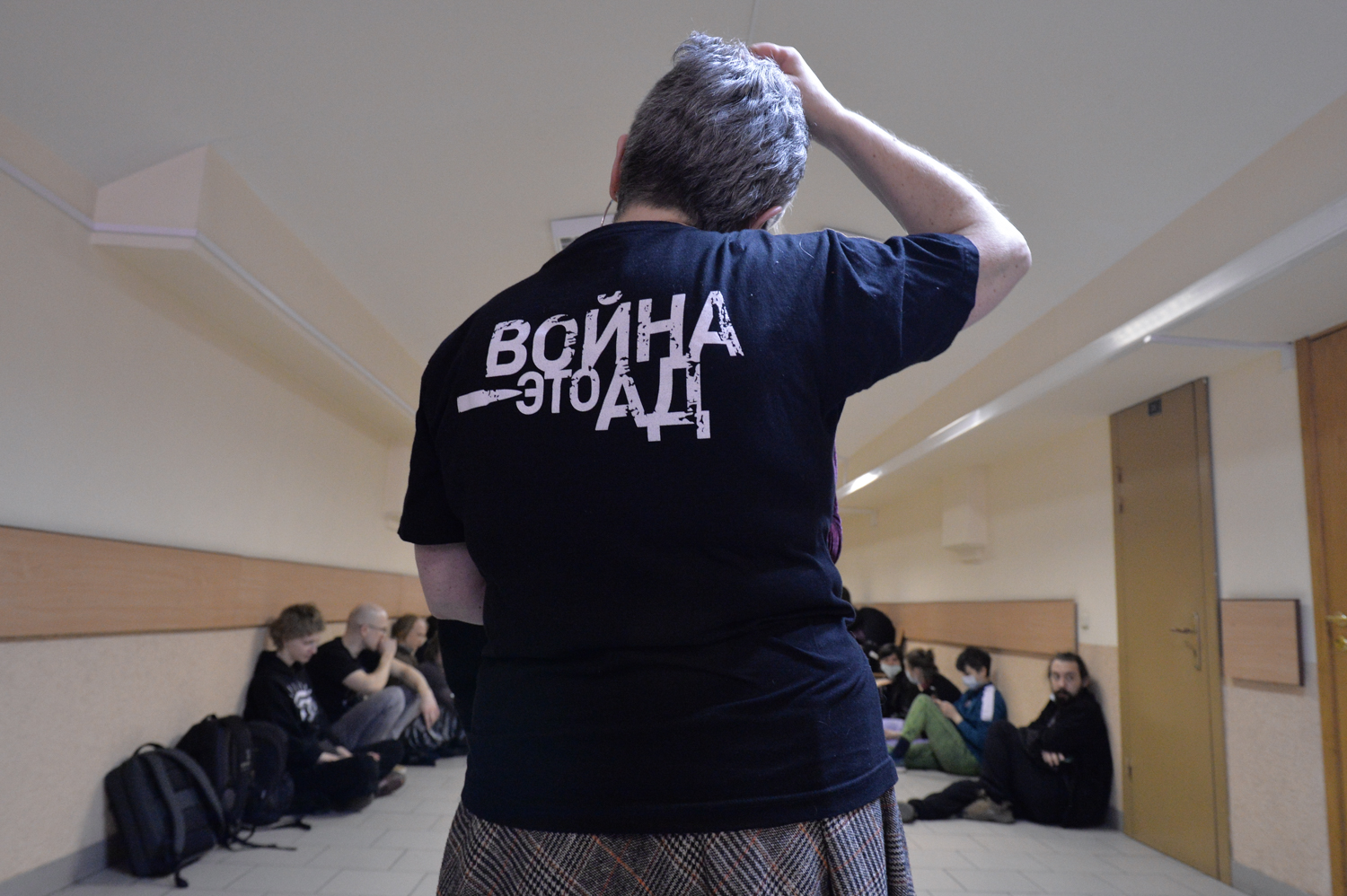

Court hearing to choose the measure of restraint began at 9 AM on April 13 in Vasilievsky Island District Court. Over forty people showed up, including Bumaga’s reporter, Sasha’s friends, independent and pro-government journalists, civil and human rights activists.

Handcuffed Skochilenko was guarded into the courtroom and put into a cage box. Visibly exhausted, she asked for some water to drink. The court did not have any and a bottle was passed from someone in the public. In her poor condition Sasha was expressing gratitude to those who came to the hearing.

“I didn’t expect this much support or such a turnout. Everyone here has been telling me that speaking out for peace is a bad thing, but the support I’m receiving is proof that it’s not. That’s the most important thing for me,” Sasha told Bumaga before the hearing.

Assigned to Sasha’s case was justice Yelena Leonova: a judge with over 20 years of experience who had been appointed to the district court in 1998 under president Boris Yeltsin’s decree.

Leonova has had a positive reputation in the media; Saint Petersburg judicial qualifications commission has also given her a high opinion. Notably, Leonova has in the past dismissed requests to arrest activists and protesters, unlike most of her colleagues. She has not, however, been clear of controversial cases and decisions.

What do we know about justice Yelena Leonova? Five notable cases ↓

The case of St. Petersburg journalist Kirill Balberov

Investigators claimed that Kirill Balberov, a journalist from Saint Petersburg, had under false pretenses received money sums ranging from 1,700 to 50,000 rubles from 22 people. In 2009, Balberov collected donations for medical treatment of a young girl from Novgorod Oblast, and before that he had been raising funds for a François Rabelais Education Club that he had established. Investigators insisted both campaigns were fraudulent. At the trial Balberov claimed the moneys had been returned to donators, which the offended parties denied. He admitted guilt but later claimed in an interview that he had to do so under pressure. Yelena Leonova sentenced the journalist to three years of suspended imprisonment.

The case of Fininvest

In May 2015 Leonova sentenced Natalia Gromova, former chair of the board at Fininvest Bank, to 3,5 years of suspended imprisonment; the bank’s former executive chair Valentin Landgraf received a suspended sentence of 4 years. They were found guilty of embezzlement totaling 1,8 billion rubles. According to the investigation, Gromova had been stealing money through fraudulent deals involving Fininvest’s employees. The bank’s license had been revoked in 2014 due to false accounting records.

The case of artist Larisa Kirillova

In 2017 the judge convicted the renowned artist Larisa Kirillova of embezzlement and gave her a suspended sentence of five years in prison. Investigators claimed that Kirillova, as the Ioganson Art School’s principal, had misappropriated 100 million rubles of public funds allocated for reconstruction of an art center in Yukki. Kirillova had already been tried and found guilty by justice Anatoly Kovin in 2016, but the sentence was later revoked and the case remanded for a new proceeding. Leonova’s ruling was the same as Kovin’s.

Cases following “He’s not Our Tsar” protests

Yelena Leonova’s name was mentioned by Zaks.ru among justices holding pleas after the mass protests under the slogan “He’s not Our Tsar” on May 5, 2018. According to the publication, Leonova’s rulings were seen as relatively “humane” by rights advocates and the Saint Petersburg legislature representative Boris Vishnevsky, as none of the protesters were arrested, unlike in other district courts. 13 detainees were punished with fines of 10,000 rubles each for illegal protesting, while 12 of them were additionally fined with 500 rubles for resisting the police.

The case of politicans’ portraits at a cemetery

In September 2019 Yelena Leonova was assigned to a criminal case of desecration of graves. An unknown individual had placed photographs of Vladimir Putin, Dmitry Medvedev, St. Petersburg Governor Alexander Beglov, Head of Chechnya Ramzan Kadyrov, propagandists Vladimir Soloviev and Olga Skabeeva, and pro-government musician Timaty onto tombstones at Smolenskoye Cemetery.

The police suspected Pavel Ivankin, an activist of the AgitRossiya movement, who had posted photographs of the tombstones at the movement’s channel on Telegram. Ivankin denied involvement, claiming that he had not been to the cemetery and was staying at home on the day in question. The police and prosecution insisted on placing Ivankin under arrest, which Leonova denied, citing lack of evidence. What came of the investigation is unclear in open sources; no charges were ever pressed against Ivankin.

In Sasha Skochilenko’s case the judge chose to side with the prosecution. Yelena Leonova’s first decision was to prohibit taking photographs in the courtroom. She then sustained the prosecutor’s motion to close the hearing from the public citing “records of witness interviews to be heard.” The only motion requested by the defense in the presence of the public was to let Skochilenko out on bail with a restraining order or under house arrest at the very most.

The hearing proceeded behind closed doors for almost five hours. Justice Leonova allowed a few journalists in the room for the verdict’s pronouncement, including Bumaga’s reporter. “Skochilenko was found to have intentionally placed pieces of paper around the merchandise space containing deliberately false information [about the Russian Army’s actions],” the judge said in her opening remark.

In her fast speech the judge made no clear distinction between the prosecution’s position and her own. “Misleading the public in regard to the Russian Federation’s military force’s [operations] is a source of tension in the society and a subversive activity,” she said.

Justice Leonova cited several reasons to put the defendant under arrest. Among other things she mentioned that Sasha:

- was charged with a grave crime against social order;

- “is able to exert pressure”

- refused to tell the passcode on her phone to the police;

- could “destroy evidence” if released;

- “has a sister in France”

- “has friends in the Ukraine”

- “is able to obstruct collection of evidence and flee to the Ukraine”;

- is registered in Saint Petersburg but lives in a rented apartment with a friend who has no necessary documentation to prove legality of Sasha’s being held under house arrest in the property; the friend could also change her mind.

The judge emphasized that Skochilenko “had visited friends in the Ukraine”. In fact, a friend of Sasha’s told Bumaga, she visited Ukraine in 2020 to teach animation to children in a summer camp.

Leonova also cited Skochilenko’s having been “detained for organizing mass gathering during the pandemic.” Sasha’s friend confirmed to Bumaga that she was detained during an anti-war protest on March 3. On that occasion Skochilenko spent a night at a police station and was fined 10,000 rubles. Sasha challenged the decision, which was upheld by an appeals court.

The judge disregarded Sasha’s diagnoses with bipolar affective disorder and celiac disease—genetic gluten intolerance, which necessitates a rigid diet—as reasons to keep her out of jail.

Yelena Leonova specifically mentioned that Skochilenko “had not been diagnosed with severe illness” and that “there was no data to indicate that [she] was in need of urgent medical treatment.” Sasha’s attorney reminded the judge about the medical records of Sasha’s condition he had earlier provided, to which Leonova said the document had been “dismissed because the source of information had not been indicated.”

How dangerous is it to be in jail with a celiac disease? ↓

Genetic gluten intolerance is not in itself a legal cause to prohibit arrest, but detention can be harmful for those affected by this condition. Gastroenterologist Alexei Golovenko told Bumaga that the disease requires a rigid gluten-free diet even with modern advances in healthcare.

“Gluten-free diet isn’t very realistic at a detention center or a holding cell. It’s unlikely that [Sasha] will want to have bread, but sausages, biscuits [common in Russian penal facilities] and many other foods contain gluten as well,” he said.

According to the medic, without a special diet Skochilenko risks iron deficiency, calcium absorption deficiency, weight deficit and reproductive depression.

Justice Yelena Leonova ruled that Sasha would be kept at the 5th Detention Center until May 31. Inside the courtroom the decision was met with tears from some and assurances to Sasha that everything was “going to be alright” from others, while those in the hallway loudly shamed the judge. Sasha smiled and waved to her friends as the public was leaving the room.

“The war will be over and I’ll be pardoned,” she said to her friend before bailiffs saw the man out.

Sasha is an artist and musician. She wrote “A Depression Book” and filmed civil protests for Bumaga. Her supporters are numerous but pessimistic

“Of all my friends Sasha is among the most talented,” says Skochilenko’s friend, journalist Arseny Vesnin. “The first time we met was about fifteen years ago. We were both in Mind Game, the [Saint Petersburg based TV network] Fifth Channel’s debate show for school students. Sasha was… I mean, she is, I sound like an obituary already—Sasha is very intelligent, talented and well-read.”

Sasha was born on September 13, 1990, in Leningrad. At 17 she entered the Saint Petersburg Theater Academy’s directing program but dropped out in her final year and was admitted to the Saint Petersburg University’s Liberal Arts and Sciences Department. She studied anthropology and graduated with distinction.

In 2013—2015 Sasha made videos of civil protests for Bumaga.

Bumaga’s CEO Kirill Artemenko says that “Sasha is a ‘good human being’ from Andrei Platonov’s books. Platonov’s characters do good without really thinking about themselves as good, without expecting kindness in return or being hurt by evil. Such people are hard-working and persevering. They may seem weak, but prove very strong. Their strength is in their principles and their natural, innate kindness.”

After developing cyclothymia—a milder form of bipolar affective disorder—she created “A Depression Book” to support people with similar conditions. The book has been translated into English and Ukrainian. Bumaga wrote about Sasha’s fight with her illness in detail.

More recently, Sasha has been making videos of lectures at the Rebra Evy [Eve’s Ribs] feminist center and doing repairs and renovations for women who feel uncomfortable hiring male workers, according to a friend of Sasha’s. She was also a manager at a children’s center at Vasilievsky Island. “She gets along well with kids, not so much with cops,” he told Bumaga.

The friend says that Skochilenko has never been interested in making a career, but rather wanted to do good and live on whatever she could earn.

As Sasha herself put it in 2020 (at the time she was making herself a living babysitting), “I don’t have a profession to speak of. I’ve been described in interviews as “a Saint Petersburg artist”, an animator, an actress, the list goes on. I don’t want to be in any particular trade. And I’m not.”

Sasha has always been passionate about music, according to her friends. She sees music “as a liberating tool,” says Skochilenko’s friend Alexei Belozerov.

“She wants to create spaces of freedom with music: without the hierarchies that always form within a musical collective, without [dividing into] performers and listeners,” says Alexei.

Another friend who has collaborated with Skochilenko in musical events says that the central idea of Sasha’s music is free improvisation, seen as an opportunity “for people who have no musical education but really want to play to take instruments and play together”. To give an example, the friend told us about jam sessions organized by Sasha at children’s psychiatric institutions as a form of art therapy.

Sasha has kept vocally advocating her notion of freedom after February 24. On the first day of the invasion she wrote on her Instagram: “I don’t support the war in Ukraine! I took it to the streets today to say that out loud. Two years ago at a summer camp in Ukraine I taught children how to make videos, I remember each of their faces. They aren’t any different from the kids I meet in Russia.”

Despite the risks, Sasha decided against emigration. According to Skochilenko’s friend Arseny, “Sasha said she wasn’t going to leave because her social capital is here, St. Petersburg is her city and Russian is her language. She’s not the kind of person whose aim is to fight the government. But she has conscience and couldn’t be indifferent to the shamelessness that’s been going on in Russia.”

Bails for Skochilenko were provided by representatives Boris Vishnevsky and Mikhail Amosov of Saint Petersburg Legislature, politician Lev Shlosberg and municipal representative Sergei Troshin. A good conduct certificate from Bumaga’s CEO Kirill Artemenko was also submitted to the court. Hundreds have posted about the investigation on social media describing the case as absurd. It has been covered by the few remaining independent media, and Bumaga has heard of actions in Sasha’s support in London.

Legal prosecution for expressing anti-war sentiment is in itself a reason for outrage, but its main factor is the potential severity of punishment—up to 10 years in prison—and the fact that Sasha has been kept in pre-trial detention despite her medical condition.

“I just want to remind you that the threats to cut heads off were never prosecuted,” wrote city representative Boris Vishnevsky, referring to the recent scandal involving Ramzan Kadyrov’s sidekick, Chechnya’s representative Adam Delikhanov of the State Duma.

“Neither were two attempts on the life of my friend [politician] Vladimir Kara-Murza. But an anti-war protest is a way to jail and then to ten years in prison. Feel the difference.”

Sasha’s supporters who talked to Bumaga remain largely pessimistic. Vishnevsky told Bumaga he “wished he was wrong” in expecting a negative outcome. Journalist Arseny Vesnin says he knew Sasha was going to be kept in detention although he did not want to believe it.

“We need to pray for the war to end, but also for a change in our own country. That’d be a good scenario. That said, nothing I can see coming is a really good scenario,” said Vesnin.

A friend of Sasha’s who actively supports her freedom told Bumaga that he could not express his true attitude to everything that is happening, including this case, without breaking current laws.

He shared his thoughts on the condition of anonymity: “This is state terrorism, unleashed, as the word implies, in order to intimidate. To maintain an atmosphere of dread. This is the only explanation why, on the account of someone’s changing one piece of paper with another in a grocery store, a bunch of people in uniforms spend a month writing reports in bundles, conducting an investigation, laying an ambush. This case and its prospects are as bleak as everything that’s going on around here. Terror will increase and deepen, they will keep intimidating us.”

Sasha is not the only one investigated. Many of those who joined the price label action are also prosecuted

As of April 7, four days before Sasha Skochilenko was arrested, 21 criminal cases had been opened on “fake news” charges, according to a post by civil rights advocate Pavel Chikov. In all but five of these cases “deliberately false information” was posted online, and just one other investigation also deals with messages distributed in a supermarket.

Some of these cases↓

Скрытый текст

- Baza reported that Andrei Samodurov, an employee with the Ministry of Emergencies in Yalta in Russian-controlled Crimea, was going door to door to warn residents about a rushed evacuation, saying that “the US have already sent their missiles and their planes and explosions are imminent in Crimea.” A criminal investigation was opened, but it is unclear which part of the Criminal Code’s new article was invoked.

- According to the Net Freedoms Project, the article’s part 2, same as in Skochilenko’s case, was triggered to investigate Sergei Klokov, an officer at the police headquarters in Moscow. Pavel Chikov reported that the man had “discussed military action in Ukraine” in a telephone conversation.

- Chikov also reports that Alexandr Tarapon from Alushta, also in Crimea, is the subject of another “fake news” investigation. The man allegedly posted anti-war stickers around his neighborhood. There is no information on which part of the article is invoked.

- The case of Penza school teacher Irina Ghen has been widely discussed in Russian media. The woman discussed the war with eighth-graders saying: “They wanted to come to Kyiv and overthrow the government. But [Ukraine] is a sovereign state with a sovereign government. […] We live under a totalitarian regime, you know. All dissent is considered a thought crime. We’re all going away for fifteen years.” The students recorded her speech and passed it to the police. The charges were pressed according to the article’s part 1.

- Like Sasha Skochilenko, Smolensk resident Vladimir Zavialov is investigated for pacifist messages inserted into supermarket label holders. Unlike in Skochilenko’s case, part 1 was triggered.

In spite of increasing pressure, false labels remain a popular way of protesting against the war. This kind of a “silent protest” is considered an effective venue of telling the truth about Ukraine to people who otherwise stay within an “information bubble.”

This initiative gained momentum after it was promoted by the Feminist Anti-War Resistance, a movement launched within Russian feminist community in February 2022 after the invasion began. Members of the movement acknowledge that protesting involves risks.

The movement’s representative tells Bumaga that “the police have been increasingly active in tracking down people involved in all kinds of anti-war protests. We have information that one of our members who posted messages on labels was tracked down using her credit card data, which she used to pay for her groceries.”

The movement’s activists say they have never talked to Skochilenko, at least not knowingly (communication is largely anonymous). However, they readily express their support of the artist: “We think they must let Sasha go, have her case closed and all charges dropped.”

“Anti-war labels are a popular way of protesting alongside stickers and leaflets distributed in public spaces. There is, unfortunately, no safe way to protest against the war in the current situation in Russia. We make it a point to remind activists about that and we are urging everyone to consider safety measures and remember the risks.”

Two days after the trial, Sasha Skochilenko is still in a holding cell. The woman will be transported to a detention center in the afternoon. Through her lawyer, Sasha has informed that she is fine and grateful to everyone who supports her.

The holding facility’s administration promised to arrange a gluten-free diet for Sasha. Her attorney says they kept their promise, and a similar request has been made to the detention center. In the meantime, Sasha’s girlfriend has been summoned for questioning to the Investigation Committee.

Bumaga will keep following the case of Sasha Skochilenko.

Liked the article? Tell your friends on Facebook